Hollywood as a collective definition is composed of several large interlocking systems, all designed to create, produce and distribute entertainment content. Most are being crushed by the coronavirus lockdown. Going through the process beginning to end:

• Pre-production is still going strong. TV writer’s rooms are staffed via video conference, and scripts are still being optioned. Projects are still being greenlit, and everyone is positioning for the days that will follow COVID-19.

• Productions are dark. Thousands of film and TV show production companies are shut down, crews on furlough, sound stages empty, equipment unrented. Film and TV Production are collective endeavors, ones that require a lot of close contact (for example: during shooting, an average cinema camera rig has three sets of hands on it) so it won’t be safe for a long time. News and some forms of reality TV have the edge here: “American Idol” is experimenting with a remote contestant format, which is better than nothing.

• Live theater is utterly dark. Hamilton is playing at precisely zero venues worldwide.

• Streaming services and cable are doing incredible business right now. Industry leaders are worried about the medium-term health of this sector: If the astounding level of unemployment continues, subscriptions to streaming services and full-service cable will start to dwindle as people find them increasingly unaffordable.

• The big hit to Hollywood: Film Exhibition. Movie theaters are closed, and the prospects of movie-going returning to prior levels any time soon is increasingly uncertain. In fact the very survival of movie theaters is in doubt: AMC may be looking at bankruptcy protection (something they do once a decade or so, but still).

Movie-going has been derided constantly in the age of streaming as a dinosaur, a relic of the pre-television industry. This is what most of this post is going to concentrate on, because I do not think people really grasp how absolutely vital the movie theater ecosystem is, and how losing them will profoundly affect almost every other aspect of the entertainment industry.

Studios operate on a “tentpole” model: big, well-publicized films released to thousands of theaters worldwide and provide revenue through box office sales for other productions. To turn a profit for these films, which are generally budgeted over $100 million, huge theater capacity is required, hundreds of thousands of butts in seats. Marvel, the newest large studio, operated on the tentpole model 100%. Others operate downmarket, packaging independent films made on modest budgets.

But all this machinery has stopped.

I’m offering two prognostications for the future of the motion picture exhibition industry, both on the extremes.

FULL RECOVERY SCENARIO

When the states start slowly opening up theaters again, social distancing guidelines can be put into effect to assure patrons who are going to be VERY VERY NERVOUS about going into a darkened windowless room full of strangers.

The way I came up with (which no doubt the theater chains are implementing) is centered around the fact that most theaters are based on reserved-seat ticket sales. When a block of seats is purchased, the seats around them are condemned for the screening to maintain a 6-foot defensive space. If strict contact rules are allowed— two parties per row to eliminate close passing for the aisle, which is always ass-to-face— theaters can be filled about 25% of capacity. This does not allow for full sellouts, but it is at least equal to a modest weekday crowd.

During these first few weeks or months people will likely be treated to low-budget fare. Independent films, genre comedies, horror films: films with modest budget and the possibility of getting a return even in lower-capacity venues. Studios can and will reserve their large-budget tentpole films until they can get enough screening capacity to make releasing them a worthwhile risk. (a lot of big-budget films are frozen in post-production as well: visual effects houses are not operating, and a film the scope of something like Avengers: Endgame can’t be finished off on somebody’s iMac at home.)

Once the curve is safely flattened theaters can go back to full capacity, though it remains to be seen if people will feel confident enough to pack themselves into sellouts for quite a while. Some late-summer big-budget releases— the sequel to Wonder Woman being an example— are sticking to their release dates, betting the huge audiences are just waiting for the all-clear.

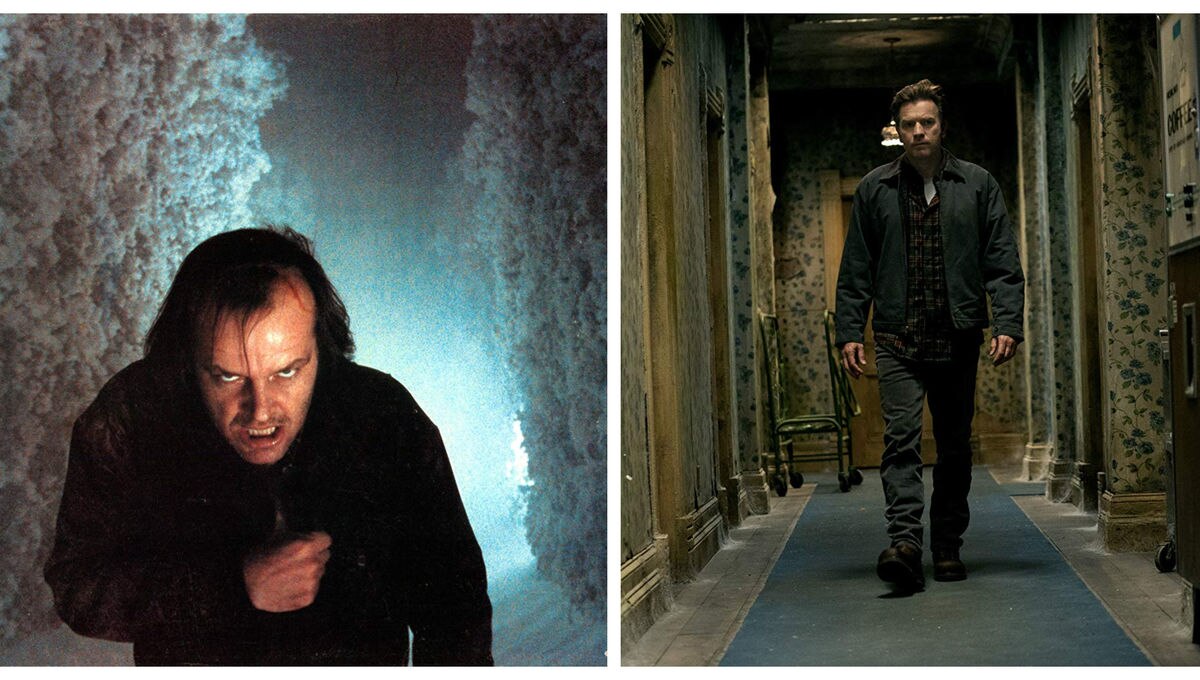

|

| Bravely sticking to a mid-August release date. Notice it's already been moved down from June. |

Major chains, empty but still paying huge rents for their their multiplexes, go out of business. Theaters that survive see persistent poor box-office as people, still spooked by COVID-19, stay away.

Without a way to recoup investment for big-budget films, the studios release them streaming at a loss. Streaming and on-demand represent a revenue source, but compared to theatrical release box office it’s tiny, ancillary, in the old days a way to slightly round up the numbers.

If the financial downturn continues and people cancel subscriptions, even this outlet will become even more problematic. Without a path to profit studios will eventually stop green-lighting big-budget films entirely. For movie geeks who hate comic-book movies this sounds heavenly, but remember that big films finance small films. The Lord of the Rings trilogy financed a decade’s worth of modest-budget New Line films.

Without theaters, the theatrical distribution system will collapse. This will create chaos: non-chain theaters that managed to stay open will have nothing to screen. Drive-in theaters, the only healthy subsection of the exhibition industry, will collapse as well when they run out of films to screen.

This bleak scenario ends on your TV: Streaming, on-demand and TV will be the only outlet for scripted entertainment. The big franchises will likely be broken up into series and miniseries. Cable and premium, already increasingly turning to series to attract viewers, will start to shrink: many of the add-on premium channels show endless theatrical films, and with that source of content gone add-ons like Starz Action and Showtime Comedy will start vanishing.

The other problem is the eternal conflict: Hollywood versus The Internet. If the theater industry collapses, the Internet wins— and never forget the old hacker battle cry: “The Internet wants to be free.” People naturally EXPECT films to be cheap or even free when they’re on TV. Additionally, any film put out on streaming is available for torrent download within hours. In my job as a post-production profession I’ve always advised indie filmmakers to only put your films on streaming platforms when all other revenue streams— festivals, optical media— have been exhausted. Once it’s online, you’re done making money off it.

But with all the eggs in the TV screen basket we’re back to the ability of people to pay for these services. If hard times persist, many of them will end up cancelling, which will drive revenue even lower.

Well, those are the extremes. I think the reality will be somewhere in-between: some chains will close, some big-budget films will be canceled, and it’s going to be tough to make a living in Hollywood for a while.

But really: nobody knows anything.