Monday, December 30, 2019

Monday, December 23, 2019

CatPile

Allow me to quote myself, standing in the lobby of the Burbank 16 after a screening of Cats last night:

"Did I ever tell you about that time I watched an episode of American Idol on acid?"

Skot, the wise solon who runs this blog, insisted I elaborate so I'll go on. For starters, I was kidding. Anybody who has been around me knows I would never, EVER, go near that stuff. And all other reality shows.

But I'm familiar with American Idol in form, and I think if I ever did watch it on acid it would be no different an experience. Whatever narrative Cats can claim boils down to this: Cats introduce themselves via song and dance, then there is a Judge who listens and decides which of them is the most "jellicle" and worthy of rebirth and ascension to the "heavyside layer". If that judge is Simon Cowell or someone more literally catty, doesn't matter.

Just to add a few other things to the massive library of derisive online comment about this movie: I think they have rolled out the CGI corrections to the theater I saw this at. A lot of early reporting says that Dame Judi Densch's real hand figured prominently in one of the shots near the end of the movie and I don't remember noticing. Though honestly I was pretty stunned at that point and I was just accepting anything they threw at me. (They have cat feet AND they wear taps? Fine!) Also I confess I teared up when Grizabella sang her solo. I may have have just been having a breakdown that coincided with the timing of the song.

The theater was only about a 1/3 full and I am certain that it was all people like me who were seeing it because they'd heard it would melt their brains. Almost everything that happened was accompanied by cries of NO NO and peals of laughter. It's very awfulness is a participation gimmick after only 3 days in release, and that's a kind of record.

Let's close with a joke.

This songwriter is meeting another songwriter for lunch at a bistro right outside the 2nd songwriters 5th floor apartment building. The first songwriter (let's call him AAB) is sitting outside with a glass of water and looks up to see the other songwriter (ABA) waving from his balcony. ABA leans too far and tumbles over the railing, plummeting to the street. But he hits an awning at floor 3, which breaks his fall; however he rolls and arcs off right toward the road. But just as he reaches terminal velocity he strikes a pickup hauling mattresses, and bounces harmlessly to land literally in his chair, right across from AAB.

"Wow! Are you lucky!" says AAB

ABA thinks for a moment. "No," he says. "Andrew Lloyd Webber. HE'S lucky."

The point is, Hollywood had been able to avoid making this movie for over forty years, and it's certainly due to the fact that nobody, NOBODY, understands how it could have been a hit in the first place. The film industry should have not tried to solve that mystery. You know what they say about curiosity.

"Did I ever tell you about that time I watched an episode of American Idol on acid?"

Skot, the wise solon who runs this blog, insisted I elaborate so I'll go on. For starters, I was kidding. Anybody who has been around me knows I would never, EVER, go near that stuff. And all other reality shows.

But I'm familiar with American Idol in form, and I think if I ever did watch it on acid it would be no different an experience. Whatever narrative Cats can claim boils down to this: Cats introduce themselves via song and dance, then there is a Judge who listens and decides which of them is the most "jellicle" and worthy of rebirth and ascension to the "heavyside layer". If that judge is Simon Cowell or someone more literally catty, doesn't matter.

Just to add a few other things to the massive library of derisive online comment about this movie: I think they have rolled out the CGI corrections to the theater I saw this at. A lot of early reporting says that Dame Judi Densch's real hand figured prominently in one of the shots near the end of the movie and I don't remember noticing. Though honestly I was pretty stunned at that point and I was just accepting anything they threw at me. (They have cat feet AND they wear taps? Fine!) Also I confess I teared up when Grizabella sang her solo. I may have have just been having a breakdown that coincided with the timing of the song.

|

| I have developed a crush on Francesca Hayward, who plays the kitten Victoria. |

Let's close with a joke.

This songwriter is meeting another songwriter for lunch at a bistro right outside the 2nd songwriters 5th floor apartment building. The first songwriter (let's call him AAB) is sitting outside with a glass of water and looks up to see the other songwriter (ABA) waving from his balcony. ABA leans too far and tumbles over the railing, plummeting to the street. But he hits an awning at floor 3, which breaks his fall; however he rolls and arcs off right toward the road. But just as he reaches terminal velocity he strikes a pickup hauling mattresses, and bounces harmlessly to land literally in his chair, right across from AAB.

"Wow! Are you lucky!" says AAB

ABA thinks for a moment. "No," he says. "Andrew Lloyd Webber. HE'S lucky."

The point is, Hollywood had been able to avoid making this movie for over forty years, and it's certainly due to the fact that nobody, NOBODY, understands how it could have been a hit in the first place. The film industry should have not tried to solve that mystery. You know what they say about curiosity.

The Rise of Skywalker: The Fall of In Media Res

The Rise of Skywalker is a perfectly fine entry into the canon. It’s tightly scripted and beautifully rendered, full of consequential situations and lots of action. It tells the story of the ragtag Resistance movement— still very reduced in size since the end of The Last Jedi— trying to find a hidden area of the galaxy where the “Final Order”— the successor to the First Order— is amassing a new fleet, lead by none other than Emperor Palpatine himself, back from the dead. It’s a complex goal, and it sets our heroes Finn, Poe and Rey on a literally non-stop quest. Meanwhile, Kylo Ren (Adam Driver, just an amazing actor) is on a singular collision course with Rey, who he wants to come over to the Dark Side. The film is full of neat cameos, some genuine surprises— and if you have been onboard with this franchise you’ll get a little weepy at the end. A fitting end to a truly spectacular franchise.

In broad strokes, Daniel is correct: The Rise of Skywalker is basically The Return of the Jedi after the application of Daniel's Remake Formula. The major story beats are pretty much the same. But without George Lucas mucking the thing up with Ewok kiddie pandering and a static mentor-father-son conflict at the center, it has been improved quite a bit.

Satisfying endings aside, one dissonant element shines through The Rise of Skywalker: the undeniable feeling of compromise, that the owners of this intellectual property are running scared. They’re scared of their own fans. They went out of their way to placate the vocal critics of the last entry, the controversial The Last Jedi, manifested as annoying notes throughout the new film. Rose, Finn’s plucky teammate, is completely sidelined. Kylo’s helmet, smashed to pieces in the previous film (and for good reason) is fixed as good as new. And there is one, huge, ridiculous erasure so egregious it made me say, “What?” out loud in a darkened theater.

Disney’s timid, full fan service approach to the IP is also evident in “The Mandalorian,” currently streaming on Disney+. In the details, the show is as rich as any canon entry, full of robots and aliens and great visual effects. But the story it tells is not nearly as rich. The premise is simple and episodic: The title character enters a situation, gets into a bit of a scrape, then gets out, ready for the next situation. It’s very 1970s-TV-like: It reminded me of the Bixby/Ferrigno “The Incredible Hulk” or (as John pointed out) “Kung Fu.” I’m not caught up and I’ve already seen story lifts from Shane, Seven Samurai and The Unforgiven. “Baby Yoda” is drawing all the attention now as only a beloved character redesigned as a tiny, high-eye-to-face-ratio character can, but it’s now depressingly clear this show is going out of its way not to stray from rote recitations from canon.

This need for fan service is why the most hilarious goof that ever appeared in any Star Wars film had to be ruined. Near the end of The Empire Strikes Back, when Lando Calrissian announces the evacuation of Bespin, we see in a crowd panic scene a guy carrying a plastic ice cream maker. It’s a bucket with a bar on the top to carry the inner container. They were common: I ate a lot of ice cream that came out of those things in the 1970s. It was very obviously thrown in so an extra could have something to do with his hands.

In episode 3 of “The Mandalorian” we see the title character get rewarded for a successful bounty job with stacks of special steel carried in a round bucket with a base on top. It even has a name: a "camtono." In this universe an ice cream maker is actually a safe, apparently. Goof erased.

What happened? As much as I’d like to blame Disney, I think 42 years of fandom has loved this franchise to death.

Consider the first film-- from a 1977 viewpoint. For kids and grownups who liked genre sci-fi films, Star Wars was an utter shock. The film BEGAN in the middle of a great space battle, and we were quickly introduced to a cast of androids and robots and a masked villain and a princess. As the story unfolded George Lucas refused to explain a single thing. Laser swords? Superluminal travel? A giant monkey dog thing? Nope, we were left as clueless as if we were randomly dropped into an exotic foreign city without a guidebook. The only explanations we were given about anything were plot points, usually one-on-one efforts to convince people to do things: to get Luke to leave his home, Leia to give up the rebel base, to get Han to rescue Leia, etc. But the super-weird stuff? Just a given. Pre-“Episode IV” Star Wars was perfect expression of in media res ("in the middle of things"): An entire self-contained universe we got to run around in for 135 minutes, which was a big part of the thrill. It hooked a lot of people, me included.

Ten years prior “Star Trek” had done something similar in science fiction, but that universe was our universe, just in the future. But know one thing about the humans in the Star Wars universe: they look like us, are similar to us in most ways… but they aren’t us at all. The opening title card “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…” has never been explained.

Star Wars was a huge success, and it spawned a dedicated fanbase: a sequel HAD to be made, even though the first episode had a tight ending and only one open end (Darth Vader survived). This sequel— The Empire Strikes Back (1980) was remarkably good. Written by Lawrence Kasdan and Leigh Brackett, It matured the space-opera story of the first movie, introduced romance and mysticism and had a plot with genuine consequences. It also had the best final reveal in any popular film, maybe ever. It was a triumph, not only because it was not the “Star Wars Goes Hawaiian” sequel everyone expected, but it rewarded every fan, deepening their relationship to the franchise AND raising their expectations.

Like I said, Empire was good. Maybe too good: It raised fan expectations so high the franchise had nowhere go but down. This may well have been the place where fandom began to fray, leading to the awful state it is in today.

The ecstasy of fandom is how it creates personal meaning and forges communities. But the tragedy of fandom is this emotional satisfaction comes with a relentless need to identify, classify and explain. Humans are pattern-seeking, storytelling creatures: it's our nature. To draw deeper meaning from a hermetic work like the original Star Wars, we needed all those mysterious little details explained so we could feel more at home there.

When the second set of trilogies came around, George Lucas adamantly refused to bow to fan service. His ideas concerning his own creation had changed and matured between 1983 and 1999, and he had whole host of things to say, some of them quite bizarre. He wanted to explain things, but he did it with complex political discourses and the added existence of a symbiotic organism which “gave” people The Force. He also added more of the feeble kiddie pandering he hinted at in Return of the Jedi, but to his credit he corrected it by Episode II. Lucas clearly didn’t quite understand what the franchise’s fanbase had evolved into-- and, delightfully, he really didn’t have to care.

But he eventually sold off his franchise, and the new owners— Disney— were aimed like a laser beam at giving fans what they want. The overarching theme of the entire third trilogy of Star Wars films is how their new IP has been guided by the expectations of the fan base. Every fan has a strong opinion about what Star Wars is and should be: some foolish, some nuanced. They started out strong with The Force Awakens and successfully deepened their commitment to original storytelling with Rogue One: a Star Wars Story.

But The Last Jedi was the tearing point. Rian Johnson’s film got a lot done in its exceeding length: it deconstructed George Lucas’s galaxy as a place of irredeemable corruption, where noble causes were not worth much more than the sinister ones. It pulled away from the Holy Skywalker family, establishing that Rey was a Jedi from nowhere, just as Annikin Skywalker came from nowhere. As for Luke Skywalker himself, he was disgusted with the Jedi and saw it as a pointless cult that needed to die.

There were a lot of Star Wars fans who were okay with this redefinition, mostly because it represented a fresh viewpoint, a way to appreciate this universe with added complexity and nuance.

But there were an equal number of Star Wars fans who HATED what Rian Johnson was doing, and wanted it stopped. For them, they needed the comfort of a black-and-white universe. They needed the saga to be about powerful families: the galaxy far, far away was to be administered by the Kennedys and the Windsors and the Rockefellers. They spoke loud and long, loud enough to spook the IP’s new masters at Disney. Revealing new things is anathema: they wanted stories that explained things. In media res, the style that animated the first film, was extinct by the last one.

When it came time to make Episode IX, guess who Disney listened to?

Still, I am putting in a very strong recommendation to go see The Rise of Skywalker. It is still an immensely entertaining film, especially If you have been a fan of the series. You will leave very satisfied— even if part of you will always wonder what might have been if we hadn’t screwed it up.

In a strange, roundabout way the evolution of Star Wars fandom from awestruck enthusiasm to toxic, second-guessing complaining is a tonic: it makes it easier to say goodbye to the franchise.

In broad strokes, Daniel is correct: The Rise of Skywalker is basically The Return of the Jedi after the application of Daniel's Remake Formula. The major story beats are pretty much the same. But without George Lucas mucking the thing up with Ewok kiddie pandering and a static mentor-father-son conflict at the center, it has been improved quite a bit.

Satisfying endings aside, one dissonant element shines through The Rise of Skywalker: the undeniable feeling of compromise, that the owners of this intellectual property are running scared. They’re scared of their own fans. They went out of their way to placate the vocal critics of the last entry, the controversial The Last Jedi, manifested as annoying notes throughout the new film. Rose, Finn’s plucky teammate, is completely sidelined. Kylo’s helmet, smashed to pieces in the previous film (and for good reason) is fixed as good as new. And there is one, huge, ridiculous erasure so egregious it made me say, “What?” out loud in a darkened theater.

|

| The Mandolorian and "The Child." This show was also influenced by the manga and film series "Lone Wolf and Cub" |

|

| Werner Herzog as "The Client," making his own German Chocolate Existential Ripple ice cream. |

In episode 3 of “The Mandalorian” we see the title character get rewarded for a successful bounty job with stacks of special steel carried in a round bucket with a base on top. It even has a name: a "camtono." In this universe an ice cream maker is actually a safe, apparently. Goof erased.

What happened? As much as I’d like to blame Disney, I think 42 years of fandom has loved this franchise to death.

| |

| This isn't the beginning of a movie: it's the middle of a complex sequence. |

Ten years prior “Star Trek” had done something similar in science fiction, but that universe was our universe, just in the future. But know one thing about the humans in the Star Wars universe: they look like us, are similar to us in most ways… but they aren’t us at all. The opening title card “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…” has never been explained.

Star Wars was a huge success, and it spawned a dedicated fanbase: a sequel HAD to be made, even though the first episode had a tight ending and only one open end (Darth Vader survived). This sequel— The Empire Strikes Back (1980) was remarkably good. Written by Lawrence Kasdan and Leigh Brackett, It matured the space-opera story of the first movie, introduced romance and mysticism and had a plot with genuine consequences. It also had the best final reveal in any popular film, maybe ever. It was a triumph, not only because it was not the “Star Wars Goes Hawaiian” sequel everyone expected, but it rewarded every fan, deepening their relationship to the franchise AND raising their expectations.

Like I said, Empire was good. Maybe too good: It raised fan expectations so high the franchise had nowhere go but down. This may well have been the place where fandom began to fray, leading to the awful state it is in today.

The ecstasy of fandom is how it creates personal meaning and forges communities. But the tragedy of fandom is this emotional satisfaction comes with a relentless need to identify, classify and explain. Humans are pattern-seeking, storytelling creatures: it's our nature. To draw deeper meaning from a hermetic work like the original Star Wars, we needed all those mysterious little details explained so we could feel more at home there.

When the second set of trilogies came around, George Lucas adamantly refused to bow to fan service. His ideas concerning his own creation had changed and matured between 1983 and 1999, and he had whole host of things to say, some of them quite bizarre. He wanted to explain things, but he did it with complex political discourses and the added existence of a symbiotic organism which “gave” people The Force. He also added more of the feeble kiddie pandering he hinted at in Return of the Jedi, but to his credit he corrected it by Episode II. Lucas clearly didn’t quite understand what the franchise’s fanbase had evolved into-- and, delightfully, he really didn’t have to care.

|

| The throne room from The Rise of Skywalker |

But The Last Jedi was the tearing point. Rian Johnson’s film got a lot done in its exceeding length: it deconstructed George Lucas’s galaxy as a place of irredeemable corruption, where noble causes were not worth much more than the sinister ones. It pulled away from the Holy Skywalker family, establishing that Rey was a Jedi from nowhere, just as Annikin Skywalker came from nowhere. As for Luke Skywalker himself, he was disgusted with the Jedi and saw it as a pointless cult that needed to die.

There were a lot of Star Wars fans who were okay with this redefinition, mostly because it represented a fresh viewpoint, a way to appreciate this universe with added complexity and nuance.

|

| Rian Johnson directing Daisy Ridley on the Throne Room set in The Last Jedi. Rian's use of red in this film was incredible. Apparently the curtains on this set were made from real red velvet. |

When it came time to make Episode IX, guess who Disney listened to?

Still, I am putting in a very strong recommendation to go see The Rise of Skywalker. It is still an immensely entertaining film, especially If you have been a fan of the series. You will leave very satisfied— even if part of you will always wonder what might have been if we hadn’t screwed it up.

In a strange, roundabout way the evolution of Star Wars fandom from awestruck enthusiasm to toxic, second-guessing complaining is a tonic: it makes it easier to say goodbye to the franchise.

Labels:

1970s,

1990s,

Canon,

Film,

Hollywood,

movies,

show business,

Star Wars,

synergy,

television

Monday, December 16, 2019

Tuesday, December 10, 2019

Tuesday, December 3, 2019

Tuesday, November 26, 2019

Wednesday, November 20, 2019

The Tarnishing

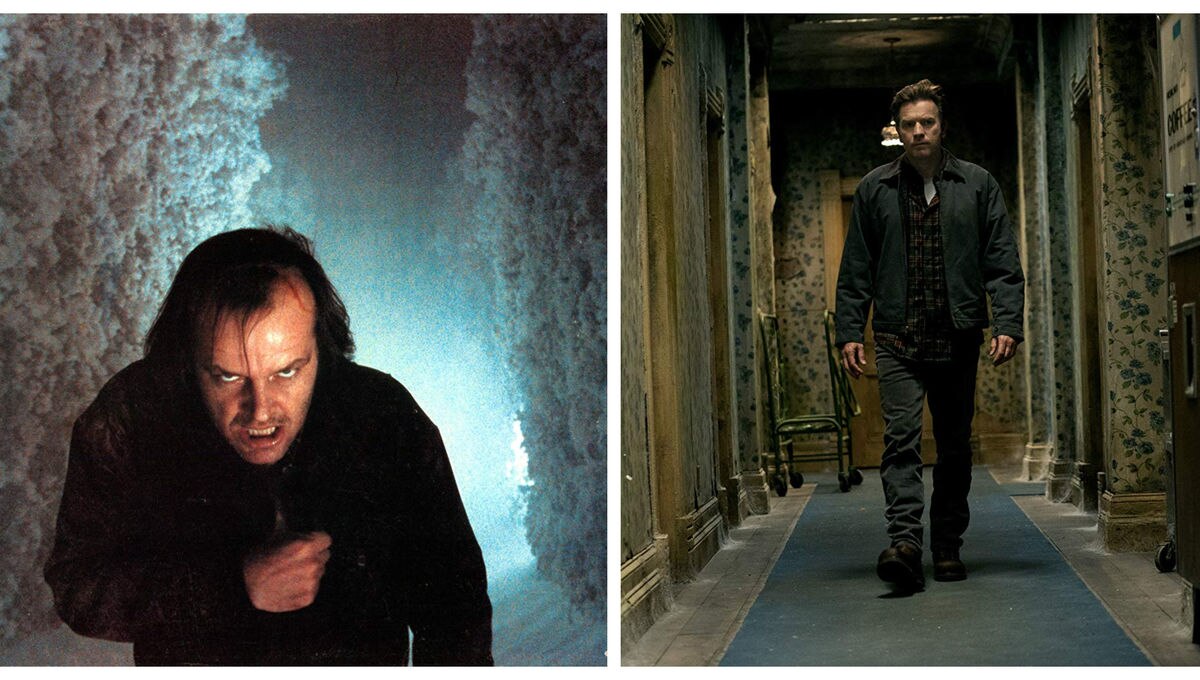

Hey, I saw Doctor Sleep this last weekend! Date talked me into it. I can't say it was disappointing because you could see that flaming train coming round the bend a mile away. I will say, though, that it made me like The Shining all the more, for the wrong reasons.

Doctor Sleep, as you know, is based on Stephen King's novel which is a sequel to King's The Shining. It details the adult adventures of Danny Torrance, the kid who escaped violent death at the Overlook Hotel when his dad Jack, to quote President Merkin Muffley, "went a little funny. In the head". Danny didn't come out of the experience unscathed. He's a depressed alcoholic who can't connect with people. But he manages to connect with a 14-year-old girl who has his psychic gift, when she enlists his help in finding and stopping the people who are killing children who ALSO have his psychic gift.

What went wrong with this thing? It's certainly well cast and shot. Ewan McGregor puts in a fine performance as a troubled American. All of the actors, in fact, are convincing. And the screenplay is competent at least. I haven't read the novel (I don't recall having read ANY Stephen King novels because he was doing fine without me) but this movie plays like a skillful adaptation of a book, brisk and faithful. Probably.

I think where we get into the weeds is the book is a sequel to another book, and this movie is ostensibly a sequel to Stanley Kubrick's movie. It's filled with visual references to the Kubrick's The Shining. And that property was NOT Stephen King's The Shining. Kubrick ground that book up and made it into some dense, multilayered crazy Kubrick lasagna, so deeply enigmatic that there's a documentary about people's varying interpretations of it. It's scary not because it's about murder and ghosts; it's scary because you're trapped inside Kubrick's head and you have no idea how to get out.

Doctor Sleep, on the other hand, is a pleasant little adventure about bad guys and good guys that is so resolutely understandable that it makes the ability to know when people are dying feel like the knowing when it's about to rain. It's not scary, it's annoying.

One of the reasons I have such fond memories of Kubrick's The Shining is because it came out a few years after MGM tried to make a sequel to another Kubrick film. 2010: The Year We Make Contact had most of the same problems that Doctor Sleep has. It's an attempt to normalize and literalize the magic of the original, and it fails because it lacks the spark of genius that made you notice Kubrick's work.

One more thing - this movie recasts the leads in The Shining with summer stock lookalikes who kind of suggest Jack Nicholson and Shelley Duvall and Scatman Crothers. There must have been better choices than these actors. Or maybe digital masks would have worked. SOMETHING. As it is I think anyone would walk out saying "I look more like Scatman than that guy."

Doctor Sleep, as you know, is based on Stephen King's novel which is a sequel to King's The Shining. It details the adult adventures of Danny Torrance, the kid who escaped violent death at the Overlook Hotel when his dad Jack, to quote President Merkin Muffley, "went a little funny. In the head". Danny didn't come out of the experience unscathed. He's a depressed alcoholic who can't connect with people. But he manages to connect with a 14-year-old girl who has his psychic gift, when she enlists his help in finding and stopping the people who are killing children who ALSO have his psychic gift.

What went wrong with this thing? It's certainly well cast and shot. Ewan McGregor puts in a fine performance as a troubled American. All of the actors, in fact, are convincing. And the screenplay is competent at least. I haven't read the novel (I don't recall having read ANY Stephen King novels because he was doing fine without me) but this movie plays like a skillful adaptation of a book, brisk and faithful. Probably.

I think where we get into the weeds is the book is a sequel to another book, and this movie is ostensibly a sequel to Stanley Kubrick's movie. It's filled with visual references to the Kubrick's The Shining. And that property was NOT Stephen King's The Shining. Kubrick ground that book up and made it into some dense, multilayered crazy Kubrick lasagna, so deeply enigmatic that there's a documentary about people's varying interpretations of it. It's scary not because it's about murder and ghosts; it's scary because you're trapped inside Kubrick's head and you have no idea how to get out.

Doctor Sleep, on the other hand, is a pleasant little adventure about bad guys and good guys that is so resolutely understandable that it makes the ability to know when people are dying feel like the knowing when it's about to rain. It's not scary, it's annoying.

One of the reasons I have such fond memories of Kubrick's The Shining is because it came out a few years after MGM tried to make a sequel to another Kubrick film. 2010: The Year We Make Contact had most of the same problems that Doctor Sleep has. It's an attempt to normalize and literalize the magic of the original, and it fails because it lacks the spark of genius that made you notice Kubrick's work.

One more thing - this movie recasts the leads in The Shining with summer stock lookalikes who kind of suggest Jack Nicholson and Shelley Duvall and Scatman Crothers. There must have been better choices than these actors. Or maybe digital masks would have worked. SOMETHING. As it is I think anyone would walk out saying "I look more like Scatman than that guy."

Tuesday, November 19, 2019

Wednesday, November 13, 2019

Tuesday, November 5, 2019

Monday, October 28, 2019

Monday, October 21, 2019

Monday, October 14, 2019

Tuesday, October 8, 2019

JOKER: Nihilism With a Purpose

How fascinating was Todd Phillips' Joker? I didn’t even realize until it was over that the movie was in 1.85:1, traditional spherical widescreen. We’re in an era where almost every theatrical film, tiny indie or major studio release, is in 2.39 ‘scope. It was presented in the period-correct aspect ratio, and the period-correct film washed over me so thoroughly I didn’t even see the frame— and I ALWAYS see the frame.

Controversy swirls around Joker like the cloud of delusions that define Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix), the movie’s antihero. we’ll get to that later, but first an appreciation of the film’s star. Phoenix was given a lot to work with here and he delivers. In truth, he over-delivers: his character is mentally ill and unknowable and his performance never deviates from this condition. This lends his story and the larger story of Joker a disjointed, alienated feel.

Arthur is a clown-for-hire who aspires to be a stand-up comedian, except his illness leaves him basically without a sense of humor. Inappropriate laughter is his illness’s major symptom: we see him in a comedy club, trying very hard to understand how comedy works, writing notes and laughing at the set-ups, not the punchlines. And his laugh is not a chilling villain’s cackle: it’s a strangled, involuntary reflex he cannot control.

Joker is set in a realistic version of a fictional past: Gotham, the East Coast city from the Batman franchise, in the late 1970s or early 1980s. It has the look and feel of the gritty “New Hollywood” films shot in New York or Philadelphia at the time: trash in the streets, tagged up subway cars, theaters downtown devoted to pornography, and there is not a computer or cellphone in sight. You will think Todd Phillips is emulating Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) to an extreme degree, and you‘d be right. But I’ll argue it’s worth it: the art direction, locations, sets and costumes are worth the price of admission by themselves. The attention to detail is remarkable and thorough. Joker only betrays its 21st-Century origins in the beauty of the images (Shot on an Arri Alexa 65) and the smoothness of camera movement (they have all sorts of magical tech gizmos to facilitate that). Back in the bad old days filmmakers like Scorsese and Melvin Van Peebles and Joseph Sargent and Gordon Parks had to make do with Arriflex IIc cameras loaded with grainy, pushed 35mm film, wooden sticks and Lowell incandescent lights.

In my opinion Joker could have dispensed entirely with the entire DC Batman mythology. The film did not need it, and it added nothing to the core of what is essentially a psychological thriller. In fact, the baggage of the Joker mythology creates an ethical issue: we know that Joker will become a master criminal and an unrepentant, cold-blooded murderer: this aspect is part and parcel of Joker’s DC persona. But remove Arthur Fleck’s known fate to be a villain, and it becomes the story of one man’s mental disintegration during an era where isolation and alienation were practically the norm.

It’s not a perfect film and it is not that easy to watch: Arthur Fleck is set up as a victim for most of it, and we see him on the ground getting his ass kicked twice. The first half of the film is set-up, and we see things in Arthur’s life, which started out bad, just get worse. The very conditions of urban life in the late 1970s are the antagonist here: Budget cut-backs eliminate Arthur’s weekly visits to a social worker and access to medication to keep his illness in check. He lives in a hideous apartment with his declining mother (Frances Conroy) in a neighborhood overflowing with trash. Adding humiliation to alienation, Arthur’s attempt at stand-up comedy is mocked by a late-night talk-show host (Robert De Niro, playing Jerry Lewis from The King of Comedy). His character is clearly being pushed towards a break with normality, and when it comes the only thing surprising about it is how gory it is.

It also makes Arthur Fleck’s eventual transformation into the Joker problematic. The film explains him away: he is the product of bad genes, a terrible childhood, an even more terrible environment, and horribly complete social isolation. This was the thrust of most of his comic-book origin stories as well: in the famous graphic novel “The Killing Joke,” The Joker is the result of one normal man after one very bad day.

At the point in the story where Arthur Fleck eventually snaps, everything in the film has been placed to make his move to villainy sympathetic. This makes Joker an exercise in pure cinematic nihilism: it’s a director deciding make a murderous villain his movie’s hero. And this is where the film goes from compelling but flawed to brilliant, because Joaquin Phoenix’s performance is the counterbalance to Todd Phillips’ nihilism. He portrays Arthur Fleck as disjointed and mercurial: his moods change from scene to scene, from somewhat sympathetic to completely alien. He leaves the audience with nothing to grab on to, which is the point. As much as the film tries to set up the origins of Joker as pitiable, Joaquin Phoenix pushes back, making sure you don’t feel shit for the guy. It is rare these days to see the an actor-versus-director dynamic play out onscreen, but that’s what we get here.

The “tell” of Joker— the element Todd Phillips and co-writer Steve Silver steered away from DC canon to stake out new narrative territory– is the portrayal of Bruce Wayne’s father, industrialist Thomas Wayne (an almost unrecognizable Brett Cullen). In the comics he is the just, benign father-figure of young Bruce, whose strong ethical sense set Bruce on the path to be a superhero. But in Joker he is a grasping, bloated capitalist who literally sneers at the poor: “Those of us who have accomplished something with our lives will always look down on those who have not as clowns.” Thomas Wayne's statement sparks deep resentment among Gotham’s beaten-down residents, and starts a clown-themed anti-establishment movement— not too far off from the Guy Fawkes thing from V for Vendetta— to topple the rich of the city.

And that is what makes Joker timely. Set in the 1970s, it nonetheless completely understands the cruelty of inequality in our time, and the fact that a society without empathy breeds monsters.

Controversy swirls around Joker like the cloud of delusions that define Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix), the movie’s antihero. we’ll get to that later, but first an appreciation of the film’s star. Phoenix was given a lot to work with here and he delivers. In truth, he over-delivers: his character is mentally ill and unknowable and his performance never deviates from this condition. This lends his story and the larger story of Joker a disjointed, alienated feel.

Arthur is a clown-for-hire who aspires to be a stand-up comedian, except his illness leaves him basically without a sense of humor. Inappropriate laughter is his illness’s major symptom: we see him in a comedy club, trying very hard to understand how comedy works, writing notes and laughing at the set-ups, not the punchlines. And his laugh is not a chilling villain’s cackle: it’s a strangled, involuntary reflex he cannot control.

Joker is set in a realistic version of a fictional past: Gotham, the East Coast city from the Batman franchise, in the late 1970s or early 1980s. It has the look and feel of the gritty “New Hollywood” films shot in New York or Philadelphia at the time: trash in the streets, tagged up subway cars, theaters downtown devoted to pornography, and there is not a computer or cellphone in sight. You will think Todd Phillips is emulating Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) to an extreme degree, and you‘d be right. But I’ll argue it’s worth it: the art direction, locations, sets and costumes are worth the price of admission by themselves. The attention to detail is remarkable and thorough. Joker only betrays its 21st-Century origins in the beauty of the images (Shot on an Arri Alexa 65) and the smoothness of camera movement (they have all sorts of magical tech gizmos to facilitate that). Back in the bad old days filmmakers like Scorsese and Melvin Van Peebles and Joseph Sargent and Gordon Parks had to make do with Arriflex IIc cameras loaded with grainy, pushed 35mm film, wooden sticks and Lowell incandescent lights.

|

| Gordon parks, making do with an Arri IIc. |

|

| Martin Scorsese, behind a soundproofed Mitchell NCR. |

|

| Joaquin Phoenix, before an Arri Alexa 65. |

At the point in the story where Arthur Fleck eventually snaps, everything in the film has been placed to make his move to villainy sympathetic. This makes Joker an exercise in pure cinematic nihilism: it’s a director deciding make a murderous villain his movie’s hero. And this is where the film goes from compelling but flawed to brilliant, because Joaquin Phoenix’s performance is the counterbalance to Todd Phillips’ nihilism. He portrays Arthur Fleck as disjointed and mercurial: his moods change from scene to scene, from somewhat sympathetic to completely alien. He leaves the audience with nothing to grab on to, which is the point. As much as the film tries to set up the origins of Joker as pitiable, Joaquin Phoenix pushes back, making sure you don’t feel shit for the guy. It is rare these days to see the an actor-versus-director dynamic play out onscreen, but that’s what we get here.

The “tell” of Joker— the element Todd Phillips and co-writer Steve Silver steered away from DC canon to stake out new narrative territory– is the portrayal of Bruce Wayne’s father, industrialist Thomas Wayne (an almost unrecognizable Brett Cullen). In the comics he is the just, benign father-figure of young Bruce, whose strong ethical sense set Bruce on the path to be a superhero. But in Joker he is a grasping, bloated capitalist who literally sneers at the poor: “Those of us who have accomplished something with our lives will always look down on those who have not as clowns.” Thomas Wayne's statement sparks deep resentment among Gotham’s beaten-down residents, and starts a clown-themed anti-establishment movement— not too far off from the Guy Fawkes thing from V for Vendetta— to topple the rich of the city.

And that is what makes Joker timely. Set in the 1970s, it nonetheless completely understands the cruelty of inequality in our time, and the fact that a society without empathy breeds monsters.

Labels:

1970s,

1980s,

acting,

Aspect Ratio,

comics,

Film,

movies,

New York City,

nostalgia,

Superhero

Monday, October 7, 2019

Sunday, October 6, 2019

Monday, September 30, 2019

Monday, September 23, 2019

Monday, September 16, 2019

Weekend Box Office

Note- if you like production value, there's even less than usual this time

CLICK HERE FOR THE REMIX BY SKOT

https://www.facebook.com/skot.christopherson/videos/2659962037381930/

Monday, September 9, 2019

Tuesday, September 3, 2019

Friday, August 30, 2019

Brush With Greatness: A Short Memoir

This true story happened in the early-to-mid-nineties, and that's important to know because the context explains a lot. Something else that you should know is I've loved bad movies almost all my life. One more thing to know is this was so important to my development that I'm astonished I haven't told this story already, but I just did a search through the archives and somehow, only now can it be told.

So, back in the nineties I used to keep a journal. It was mostly an emotional steam valve, not for anyone's consumption. But now and then I'd read a passage and think, this is good stuff! I can't publish it, of course, because it's very personal and it would ruin my life and the lives of those around me. But the idea nagged at me nonetheless. And there was a point where I realized that MS Word could export HTML without much trouble, and Apple provided we with a a little web publishing space for free. So I started publishing PARTS of my journal. I wasn't advertising it or anything. It was the web equivalent of an old couch on the sidewalk. If you happen to be in the neighborhood and you need a couch, take it away.

So, given that any post about people I knew was off-limits, I mostly published complaining about things. Maybe that would mean bad traffic or airline food to a normal man. I mostly weighed in on TV and movies.

Okay, so going all the way back to my first movie theater job, I had been stunned by TREASURE OF THE FOUR CROWNS, an early 3D effort by Cannon Pictures. It was awful. It starred Tony Anthony (an Italian with a much longer real name) but I noticed that it also starred, and was written by, a man named Gene Quintano. And throughout the ensuing decade, that name stuck with me and I watched for it, and every time he came up he was associated with a movie that I thought was terrible. (Most of them were also from Cannon Pictures, and almost everything they ever did was terrible.) But by the time I started this online journal, so-called because no one had coined "blog" yet, I was a kind of expert. A Quintanologist.

And one day I did a whole entry about how much I hated all those movies. Having gotten it out of my system, I moved on to saying nice things about Twin Peaks or something.

Then, a week later, the weird part.

I got this unsolicited email from Gene Quintano.

My first thought was OMG GENE QUINTANO IS WRITING TO ME HE'S FAMOUS HE'S A WORKING SCREENWRITER THIS IS GREAT THIS IS GREAT and that faded as I read the email and realized that he was furious with me and I had made his kid cry because the kid didn't understand why anybody would hate his daddy.

And I wrote back, respectfully and explained that I was devastated that I had caused that trouble and had no idea that he would ever see it (also that he would care about my opinion but I kept that part to myself) and I'd do anything I could to make it right. He replied! If I could write an email to his kid and explain that I didn't hate Gene, that might help. So I did. I composed a short note in which I said that Gene Quintano himself was surely a wonderful guy and I just didn't care for the movies he was associated with.

That smoothed it over, kinda. Quintano wrote back a week later and pointed out that he was only the screenwriter and he didn't make the final decisions and his drafts were much better than the movies wound up being. I suggested he direct more. He did eventually helm 4 films, Including Honeymoon Academy and National Lampoon's Loaded Weapon. You be the judge.

What's the takeaway from this? It seems like a really early example of the internet's power to magnify a grievance. I think Mr Q and I were both sucker-punched by this, which is why it became such a thing. I was a nobody pretending to be a real film critic and not realizing that I had the reach of one, as long as you were an artist Googling yourself. Eventually all "real" film critics lost their clout to this phenomenon.

Anyway, maybe I'll issue another apology to Gene Quintano every 20 years or so until one of us is dead. If it's any consolation he's made a LOT more money in this business than I have, and rightly so.

Oh, and don't get me started on Lorenzo Semple Jr.

So, back in the nineties I used to keep a journal. It was mostly an emotional steam valve, not for anyone's consumption. But now and then I'd read a passage and think, this is good stuff! I can't publish it, of course, because it's very personal and it would ruin my life and the lives of those around me. But the idea nagged at me nonetheless. And there was a point where I realized that MS Word could export HTML without much trouble, and Apple provided we with a a little web publishing space for free. So I started publishing PARTS of my journal. I wasn't advertising it or anything. It was the web equivalent of an old couch on the sidewalk. If you happen to be in the neighborhood and you need a couch, take it away.

So, given that any post about people I knew was off-limits, I mostly published complaining about things. Maybe that would mean bad traffic or airline food to a normal man. I mostly weighed in on TV and movies.

Okay, so going all the way back to my first movie theater job, I had been stunned by TREASURE OF THE FOUR CROWNS, an early 3D effort by Cannon Pictures. It was awful. It starred Tony Anthony (an Italian with a much longer real name) but I noticed that it also starred, and was written by, a man named Gene Quintano. And throughout the ensuing decade, that name stuck with me and I watched for it, and every time he came up he was associated with a movie that I thought was terrible. (Most of them were also from Cannon Pictures, and almost everything they ever did was terrible.) But by the time I started this online journal, so-called because no one had coined "blog" yet, I was a kind of expert. A Quintanologist.

|

| Gene's Acting Debut, COMIN' AT YA |

Then, a week later, the weird part.

I got this unsolicited email from Gene Quintano.

My first thought was OMG GENE QUINTANO IS WRITING TO ME HE'S FAMOUS HE'S A WORKING SCREENWRITER THIS IS GREAT THIS IS GREAT and that faded as I read the email and realized that he was furious with me and I had made his kid cry because the kid didn't understand why anybody would hate his daddy.

And I wrote back, respectfully and explained that I was devastated that I had caused that trouble and had no idea that he would ever see it (also that he would care about my opinion but I kept that part to myself) and I'd do anything I could to make it right. He replied! If I could write an email to his kid and explain that I didn't hate Gene, that might help. So I did. I composed a short note in which I said that Gene Quintano himself was surely a wonderful guy and I just didn't care for the movies he was associated with.

That smoothed it over, kinda. Quintano wrote back a week later and pointed out that he was only the screenwriter and he didn't make the final decisions and his drafts were much better than the movies wound up being. I suggested he direct more. He did eventually helm 4 films, Including Honeymoon Academy and National Lampoon's Loaded Weapon. You be the judge.

What's the takeaway from this? It seems like a really early example of the internet's power to magnify a grievance. I think Mr Q and I were both sucker-punched by this, which is why it became such a thing. I was a nobody pretending to be a real film critic and not realizing that I had the reach of one, as long as you were an artist Googling yourself. Eventually all "real" film critics lost their clout to this phenomenon.

Anyway, maybe I'll issue another apology to Gene Quintano every 20 years or so until one of us is dead. If it's any consolation he's made a LOT more money in this business than I have, and rightly so.

Oh, and don't get me started on Lorenzo Semple Jr.

Monday, August 26, 2019

Weekend Box Office Report

The beach is a place where a man can feel / he's the only soul in the world that's real

Monday, August 19, 2019

Monday, August 12, 2019

Friday, August 9, 2019

Tarantino the Nostalgic Unreliable Narrator

I went into Once Upon a Time in Hollywood expecting not to like it that much: he burned me very badly with his cute switcheroo act with The Hateful Eight, a film he touted as an epic widescreen roadshow movie but turned out to be a blood-drenched, claustrophobic indie film that had no earthly reason to be in Ultra Panavision 70.

But after thinking about it for a while afterward, I have a grudging respect for this film. Once Upon a Time is built around an original story, unusual for him: its not a pastiche or an homage or a dully executed re-make of some cheap exploitation film. It’s really him, talking directly to us and not through some faux-junk, schlocky exploitation genre— and God damn it if that isn’t refreshing. Quentin succeeds at his primary goal here: creating an alternate universe version of Los Angeles in 1969. He did a splendid job of it. The dialog is crisp, mostly lacking the big gobs of “Tarantino-speak” that bogged down earlier efforts, and the acting snaps as well. It’s a longish film, and his obsession with the trappings of the past often overwhelms his story, but more worth your time than any of his films since Jackie Brown.

On to the notes!

Nostalgia: Once Upon a Time drowns in nostalgia, aching and wistful and angry at the passage of time that erased the treasures lovingly displayed onscreen. Quentin Tarantino is a filmmaker driven by desires— obscure action cinema, violence, glib dialogue, women’s bare feet. But this time his desire is the past. His past, a past he has said was the favorite time of his childhood.

Once Upon a Time is Quentin the video-store clerk and kid who grew up in LA in the 1960s and 1970s, finally brought to his fullest. It’s a wishlist of everything he ever wanted to do in a movie as a kid, pattered out in his characteristic staccato: he wants to be a TV western star (Quentin Tarantino was named after Burt Reynold’s character in “Gunsmoke”). He wants to beat up Bruce Lee. He wants to change Hollywood history (more later). He wants to set an LP needle down right on the gap before his favorite song (this happens several times) and hear the KHJ and KFWB jingles ring out over an AM car radio again. He wants to make a movie with Steve McQueen and Michelle Phillips and Sharon Tate. He wants all he knew and saw and loved as a child returned to him.*

But most of all, he wants to go home to the past. You can feel it: his longing reaches right out of the frame. It’s all there in broad strokes: late 60s Hollywood Boulevard lovingly recreated; classic, unchanged locales like Musso and Frank and El Coyote visited. There’s a montage near the end of the film that gave one of the biggest thrills of the movie: night falls and long-gone business facades light up. There’s an old Der Weinerschnitzel, a Mission-style Taco Bell, The Cinerama Dome restored to its Pacific Theaters glory.

Tarantino is one year younger than I am, and I spent some time in LA around this time as well— down in sleepy suburban Lynwood rather than Hollywood, but I know these sights, the look and feel of the era. I’ll admit one of the strongest reactions I had to Once Upon a Time in Hollywood was a strong desire to move into this film. I didn’t want to leave. I’m not sure if 1969 was a better world than 2017, but the version he showed us was simpler, shinier, and undeniably beautiful.

Two-person, one-character protagonist: washed-up star Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio) and his stunt-double/dogsbody Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt) are the inseparable pair at the center of the film. They make a very big deal out of the fact that Rick can’t function without Cliff, and vice versa. This makes it easy to pin this relationship as a Tarantino staple, tough guy male bonding. But it goes far deeper than that. Rick and Cliff are the same character. They cannot exist outside of the definition they have for each other. The two characters span one complete male personality. Rick is insecure, weak, vain and sensitive (he cries like three times in the film), but also talented and ambitious. Cliff is taciturn, strong, highly capable and practical, but also lacks ambition to the point he is content to live in a wreck of a trailer in North Hollywood. A lesser effort would have these traits embodied in one overly complex, somewhat unbelievable character: in Once Upon a Time this one character is smeared over two individuals, yin and yang, completing each other in all ways, functioning as one complete person. This sort of split character has been done in other films, but usually the other way: in biopics they make they take handfuls of real historical figures and smoosh them into one character.

History and the Unreliable Narrator (mild spoilers): Once Upon a time in Hollywood follows three intertwining storylines, much like Pulp Fiction but without time-shifting tricks: Rick and his buddy Cliff, trying to re-start a failed Hollywood career; Sharon Tate’s arrival in Hollywood, and— lurking like an evil portent— the Manson Family, biding their time in an abandoned movie ranch in Chatsworth, waiting for their call to the stage.

Anybody familiar with recent history knows what happened the night of August 8, 1969: Four members of the Manson Family entered the house on 10050 Cielo Drive in the LA hills and murdered everyone inside, including actor Sharon Tate. Not to give away anything specific, but this is not what happens at the end of Once Upon a Time. Something completely made-up happens.

Quentin Tarantino has done this sort of “alternative historical fiction” thing before: he killed the living hell out of Hitler in a French movie theater in Inglourious Basterds. And by all means he has every right to do so: he’s the storyteller here and he has a right to re-tell historical events any way he wants to. When you get right down to it, every filmmaker who ever shot a narrative film is a total and complete liar. You can plot a line straight through the relative level of reality in any filmmaker’s work, from hyper-real (Zero Dark Thirty, The Grapes of Wrath, HBO’s Chernobyl) to utter fantasy (Toy Story 4, Lord of the Rings, Top Gun) with lots of shading in-between. And the hyper-real ones are still mostly made-up hooey.

But the tall tale Tarantino is spinning at the conclusion of Once Upon a Time does something very strange. If the terrible thing that is supposed to happen on the night of August 8, 1969 doesn’t happen, what was the point of two-thirds of the film? In other words, if you showed this film to somebody with NO IDEA of the history Quentin Tarantino is re-writing, what would she make of it? She would sit through long sequences of Sharon Tate wandering around Los Angeles, shopping, seeing herself in a movie theater in Westwood. She would see long sequences of Manson Girls wandering around Los Angeles barefoot, hitchhiking and hanging around Spahn ranch. But they never really connect: all the long minutes of foreboding and build-up are dissipated in a standard Tarantino gory ending. Our historically ignorant movie viewer would leave the screening wondering why those other sequences even exist.

Does a filmmaker owe fidelity to historical facts? I don’t know. What I do know is this film will be seen by people 50, maybe 100 years from now. The Tate-LaBianca murders will no longer be a part of living history: to these future viewers, they’ll be as familiar with the actual events as we are of the details of the murder of Stanford White in 1906. Which is to say they may very well accept Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’s ending as actual history. This is how history gets distorted: it does not seem important now, but we owe some debt to the future to tell the truth.

*Quentin Tarantino put himself in this film twice, even though he had no cameo. In one segment Rick Dalton is resting between set-ups in a western backlot set next to a precocious child actor (Julia Butters). She is roughly the same age QT would have been in 1969, and you can hear him talking through her as she engages Rick in some positive affirmation. Later in the film one of the characters announces a move to “a condo in Toluca Lake,” likely the same one occupied by Jimmie and Bonnie 25 years later in Pulp Fiction (1994).

But after thinking about it for a while afterward, I have a grudging respect for this film. Once Upon a Time is built around an original story, unusual for him: its not a pastiche or an homage or a dully executed re-make of some cheap exploitation film. It’s really him, talking directly to us and not through some faux-junk, schlocky exploitation genre— and God damn it if that isn’t refreshing. Quentin succeeds at his primary goal here: creating an alternate universe version of Los Angeles in 1969. He did a splendid job of it. The dialog is crisp, mostly lacking the big gobs of “Tarantino-speak” that bogged down earlier efforts, and the acting snaps as well. It’s a longish film, and his obsession with the trappings of the past often overwhelms his story, but more worth your time than any of his films since Jackie Brown.

On to the notes!

Nostalgia: Once Upon a Time drowns in nostalgia, aching and wistful and angry at the passage of time that erased the treasures lovingly displayed onscreen. Quentin Tarantino is a filmmaker driven by desires— obscure action cinema, violence, glib dialogue, women’s bare feet. But this time his desire is the past. His past, a past he has said was the favorite time of his childhood.

Once Upon a Time is Quentin the video-store clerk and kid who grew up in LA in the 1960s and 1970s, finally brought to his fullest. It’s a wishlist of everything he ever wanted to do in a movie as a kid, pattered out in his characteristic staccato: he wants to be a TV western star (Quentin Tarantino was named after Burt Reynold’s character in “Gunsmoke”). He wants to beat up Bruce Lee. He wants to change Hollywood history (more later). He wants to set an LP needle down right on the gap before his favorite song (this happens several times) and hear the KHJ and KFWB jingles ring out over an AM car radio again. He wants to make a movie with Steve McQueen and Michelle Phillips and Sharon Tate. He wants all he knew and saw and loved as a child returned to him.*

But most of all, he wants to go home to the past. You can feel it: his longing reaches right out of the frame. It’s all there in broad strokes: late 60s Hollywood Boulevard lovingly recreated; classic, unchanged locales like Musso and Frank and El Coyote visited. There’s a montage near the end of the film that gave one of the biggest thrills of the movie: night falls and long-gone business facades light up. There’s an old Der Weinerschnitzel, a Mission-style Taco Bell, The Cinerama Dome restored to its Pacific Theaters glory.

Tarantino is one year younger than I am, and I spent some time in LA around this time as well— down in sleepy suburban Lynwood rather than Hollywood, but I know these sights, the look and feel of the era. I’ll admit one of the strongest reactions I had to Once Upon a Time in Hollywood was a strong desire to move into this film. I didn’t want to leave. I’m not sure if 1969 was a better world than 2017, but the version he showed us was simpler, shinier, and undeniably beautiful.

Two-person, one-character protagonist: washed-up star Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio) and his stunt-double/dogsbody Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt) are the inseparable pair at the center of the film. They make a very big deal out of the fact that Rick can’t function without Cliff, and vice versa. This makes it easy to pin this relationship as a Tarantino staple, tough guy male bonding. But it goes far deeper than that. Rick and Cliff are the same character. They cannot exist outside of the definition they have for each other. The two characters span one complete male personality. Rick is insecure, weak, vain and sensitive (he cries like three times in the film), but also talented and ambitious. Cliff is taciturn, strong, highly capable and practical, but also lacks ambition to the point he is content to live in a wreck of a trailer in North Hollywood. A lesser effort would have these traits embodied in one overly complex, somewhat unbelievable character: in Once Upon a Time this one character is smeared over two individuals, yin and yang, completing each other in all ways, functioning as one complete person. This sort of split character has been done in other films, but usually the other way: in biopics they make they take handfuls of real historical figures and smoosh them into one character.

History and the Unreliable Narrator (mild spoilers): Once Upon a time in Hollywood follows three intertwining storylines, much like Pulp Fiction but without time-shifting tricks: Rick and his buddy Cliff, trying to re-start a failed Hollywood career; Sharon Tate’s arrival in Hollywood, and— lurking like an evil portent— the Manson Family, biding their time in an abandoned movie ranch in Chatsworth, waiting for their call to the stage.

Anybody familiar with recent history knows what happened the night of August 8, 1969: Four members of the Manson Family entered the house on 10050 Cielo Drive in the LA hills and murdered everyone inside, including actor Sharon Tate. Not to give away anything specific, but this is not what happens at the end of Once Upon a Time. Something completely made-up happens.

Quentin Tarantino has done this sort of “alternative historical fiction” thing before: he killed the living hell out of Hitler in a French movie theater in Inglourious Basterds. And by all means he has every right to do so: he’s the storyteller here and he has a right to re-tell historical events any way he wants to. When you get right down to it, every filmmaker who ever shot a narrative film is a total and complete liar. You can plot a line straight through the relative level of reality in any filmmaker’s work, from hyper-real (Zero Dark Thirty, The Grapes of Wrath, HBO’s Chernobyl) to utter fantasy (Toy Story 4, Lord of the Rings, Top Gun) with lots of shading in-between. And the hyper-real ones are still mostly made-up hooey.

But the tall tale Tarantino is spinning at the conclusion of Once Upon a Time does something very strange. If the terrible thing that is supposed to happen on the night of August 8, 1969 doesn’t happen, what was the point of two-thirds of the film? In other words, if you showed this film to somebody with NO IDEA of the history Quentin Tarantino is re-writing, what would she make of it? She would sit through long sequences of Sharon Tate wandering around Los Angeles, shopping, seeing herself in a movie theater in Westwood. She would see long sequences of Manson Girls wandering around Los Angeles barefoot, hitchhiking and hanging around Spahn ranch. But they never really connect: all the long minutes of foreboding and build-up are dissipated in a standard Tarantino gory ending. Our historically ignorant movie viewer would leave the screening wondering why those other sequences even exist.

Does a filmmaker owe fidelity to historical facts? I don’t know. What I do know is this film will be seen by people 50, maybe 100 years from now. The Tate-LaBianca murders will no longer be a part of living history: to these future viewers, they’ll be as familiar with the actual events as we are of the details of the murder of Stanford White in 1906. Which is to say they may very well accept Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’s ending as actual history. This is how history gets distorted: it does not seem important now, but we owe some debt to the future to tell the truth.

*Quentin Tarantino put himself in this film twice, even though he had no cameo. In one segment Rick Dalton is resting between set-ups in a western backlot set next to a precocious child actor (Julia Butters). She is roughly the same age QT would have been in 1969, and you can hear him talking through her as she engages Rick in some positive affirmation. Later in the film one of the characters announces a move to “a condo in Toluca Lake,” likely the same one occupied by Jimmie and Bonnie 25 years later in Pulp Fiction (1994).

Tuesday, August 6, 2019

Weekend Box Office Report

Monday, July 29, 2019

Monday, July 22, 2019

Monday, July 15, 2019

Tuesday, July 9, 2019

Monday, July 1, 2019

Monday, June 24, 2019

Monday, June 17, 2019

Tuesday, June 11, 2019

Tuesday, June 4, 2019

Monday, May 27, 2019

Monday, May 20, 2019

Monday, May 13, 2019

Monday, May 6, 2019

Monday, April 29, 2019

Weekend Box Office Report

Special thanks to a lighting fixture in a local sushi place for the colorful background of today's show

Monday, April 22, 2019

Monday, April 15, 2019

Tuesday, April 9, 2019

Monday, April 1, 2019

Monday, March 25, 2019

Saturday, March 23, 2019

That's "Us," all right: The Hometown Perspective

Jordan Peele's Us is in some ways an expanded version of his earlier film Get Out: it deals in the same paranoid themes of identity and replacement as his first film. The new one transcends the limitations of the first, and it’s concentration on racial messages, to explore some strange new ideas. A lot of them.

The Wilsons, a family of four headed by Gabe (Winston Duke) and Adelaide (Lupita Nyong’o) set out for a vacation in the Santa Cruz area. Adelaide was there when she was a child, back in 1986: something traumatic happened to her back then that fills her with quiet unease. Then, one night in their comfortable lake house, a family of four shows up at their driveway— nearly identical copies of them, clad in red jumpsuits, holding golden scissors. They proceed to brutalize the Wilsons, fully intent on eventually killing them, likely to replace them. Not sure how that would work: these doubles are all mute-- except for Red, Adelaide’s doppelgänger, who talks in a raspy, wounded voice, who explains that they are mirror images of the Wilsons, waiting underground their entire lives for their chance to come up into our world. Things quickly become violent, and that violence soon spreads to their neighbors' lake house, and continues to build.

Jordan Peele explores some expansive ideas in this film: it has a symbolic language that plays out stronger than the horror elements. Class (there is a very literal underclass in this universe), identity and the conditional nature of morality are strong themes. These explorations give the film a more speculative, “Twilight Zone” feel than establishing a horror film tone. Nonetheless, there are homages to the “Strangers” and “Purge” franchise, and a good-sized dose of Nihilist Austrian Horror as well. Most of all, it’s a variation of “Invasion of the Body Snatchers,” the ultimate body-horror franchise.

That’s all well and good, but what about the local angle?

Our hometown of Santa Cruz (Daniel the Box Office Report guy and I both hail from there) has been in some popular films— but it rarely gets a star turn under it’s own name. It does in Us--and a very satisfying star turn at that. In the 1980s at least, the super-duper-left-leaning city council found objections to the themes of most films that wanted to shoot there, and insisted the city’s name be stricken from the scripts. Which is why The Lost Boys is set in “Santa Paula” and Sudden Impact is set in “Santa Carla:” Creator and Killer Klowns from Outer Space aren’t really set anywhere.

The Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk is a central setting in Us (as it is in most films set in the area) and I’ll admit this new film gets something right about the place earlier films missed: it’s kinda creepy. This amusement park been around for over a century, and the places where Us was filmed are on the east end of the boardwalk, which hasn’t changed much in 40 years. The opening flashback is set in 1986: having actually been there multiple times in 1986, I can say the film gets it right, and the place is unchanged. (The only difference is there used to be very good video arcade on that end, which is not evident in the flashbacks.) The Seaside Company keeps throwing paint on the place every season, but anyone who has grown up there knows the Boardwalk is an ancient place, full of history. To walk there on a summer evening is to feel the closeness of a long past: the smell of creosote, gear oil, suntan lotion and cotton candy: the crashing surf and the screams from the roller coaster riders. As kids we all shared Boardwalk myths, whispered to each other, invariably horrific: the girl who fell from the Sky Glider. The sailor who was decapitated at the top of the Giant Dipper. Us captures this mood: timeless dread barely covered up under new paint.

One of the first shocks in Us is in the 1986 flashback, when young Adelaide wanders away from her parents at the Boardwalk. She walks by a scary-looking homeless person holding a sign with a bible verse on it (Jeremiah 11:11, one terrifying verse!). People in the audience had a visceral reaction to this guy. Having grown up in Santa Cruz, however, all I could do was shrug: In my old hometown, he’s way too common to be scary.

All good horror stories start at home, right?

The Wilsons, a family of four headed by Gabe (Winston Duke) and Adelaide (Lupita Nyong’o) set out for a vacation in the Santa Cruz area. Adelaide was there when she was a child, back in 1986: something traumatic happened to her back then that fills her with quiet unease. Then, one night in their comfortable lake house, a family of four shows up at their driveway— nearly identical copies of them, clad in red jumpsuits, holding golden scissors. They proceed to brutalize the Wilsons, fully intent on eventually killing them, likely to replace them. Not sure how that would work: these doubles are all mute-- except for Red, Adelaide’s doppelgänger, who talks in a raspy, wounded voice, who explains that they are mirror images of the Wilsons, waiting underground their entire lives for their chance to come up into our world. Things quickly become violent, and that violence soon spreads to their neighbors' lake house, and continues to build.

|

| Hi. We're not the neighbors. We're you. |

That’s all well and good, but what about the local angle?

|

| Jordan Peele and the Giant Dipper. |

The Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk is a central setting in Us (as it is in most films set in the area) and I’ll admit this new film gets something right about the place earlier films missed: it’s kinda creepy. This amusement park been around for over a century, and the places where Us was filmed are on the east end of the boardwalk, which hasn’t changed much in 40 years. The opening flashback is set in 1986: having actually been there multiple times in 1986, I can say the film gets it right, and the place is unchanged. (The only difference is there used to be very good video arcade on that end, which is not evident in the flashbacks.) The Seaside Company keeps throwing paint on the place every season, but anyone who has grown up there knows the Boardwalk is an ancient place, full of history. To walk there on a summer evening is to feel the closeness of a long past: the smell of creosote, gear oil, suntan lotion and cotton candy: the crashing surf and the screams from the roller coaster riders. As kids we all shared Boardwalk myths, whispered to each other, invariably horrific: the girl who fell from the Sky Glider. The sailor who was decapitated at the top of the Giant Dipper. Us captures this mood: timeless dread barely covered up under new paint.

|

| This is something you can see any day of the week in Santa Cruz. |

All good horror stories start at home, right?

Labels:

1980s,

amusement parks,

BO chart,

Horror,

movie,

nostalgia,

Santa Cruz

Thursday, March 21, 2019

Apollo 11: Best "Found-Footage" Doc EVER

First of all, I was there for the real thing: July 20th, 1969, when Neil and Buzz of Apollo 11 walked on the moon. A moment in history never to be forgotten or repeated, the day the cold, lifeless universe began to yield to humanity's will. I did not think in such grandiose terms at the time, of course, being seven years old-- but nothing could have pried me away from our Motorola console TV that day, not for all the candy in the world (and the candy was very good in 1969).

We had relatives over and everyone watched with wonder-- except my uncle Jim, who had a big lunch and was passed out in dad's Barcalounger, snoring through the whole thing. I was annoyed with him at the time, but now I realize he had a half-good reason to be zonked out: For such a momentous event in world history it was not a particularly interesting one to watch. Neil's step onto the lunar surface was carried live, but it was a super-contrasty monochrome image. The networks carrying the moon landing used a lot of cheesy animation, simulations and talking heads to pad out the low-res NASA video feed. The astronauts had to return to the earth, with it's plentiful film processing facilities, with magazines of exposed 16mm movie film and 70mm still images to give us the iconic imagery we associate with the era.

The media status for early manned spaceflight hasn't changed that much: Grainy 16mm and low-res video (some in color), backed up by more 16mm TV coverage. When documentary filmmaker Todd Douglas Miller set out to make a 50th anniversary tribute of the Apollo 11 mission, he started out with the same resources everyone else had since the Nixon era: The familiar stills and grainy news footage, the same warbling audio.

Then two remarkable archives of previously unseen and rarely heard content were discovered.

The first discovery was the identification, deep in the vaults of the National Archives, of 165 reels of well-preserved Todd-AO 65mm film negative documenting the Apollo missions, from 8 to 14. These had been stored-- unseen-- since they were shot. Nobody even knew WHY this incredible trove of film existed: There was a tenuous connection to a failed co-production between NASA and MGM pictures, and this precious footage may have been outtakes from this effort. It is more likely that some unknown Public Affairs Officer at NASA wanted a definitive archive document for this extraordinary moment in human history, in the highest fidelity possible. In terms of capturing detailed, realistic imagery, 65mm was about as good as you could get in the late 1960s-- The resolution is the equivalent of 13K digital, a DCP format that does not currently exist because it would melt the image processors.

The second discovery was the original 30-track audio recordings of the Apollo missions. At Mission Control in Houston all the various departments (CAPCOM, FIDO, Guidance, etc.) had their own audio circuit loops so the various members of each team could talk to each other. Other departments could punch into these loops as needed: a lot of the cool buttons on the Mission Control consoles are simply audio patch switches. These archive tape reels were digitized, corrected for various imperfections (the “wow and flutter” of the original audio made a lot of the voices on these tracks sound tremulous and nervous: now they just sound normal) and time-coded.

These new resources went into Apollo 11— and the results are nothing short of magnificent. You have never seen Apollo-era NASA footage like this before: It's crystal-clear, with vibrant, unfaded color, looking like it was shot yesterday. The vividness is startling, out of context and impossible-feeling, as if someone found super8 home movies taken during the Battle of Gettysburg. The 65mm footage in concentrated in the beginning and end of the film, the launch and all the hubbub around it, and the carrier recovery and processing afterward. There was one Todd-AO camera set up less than a mile from the launch pad (on remote control, if they were smart) and the result is the most insanely detailed look at a Saturn V taking off ever seen. It puts the digital simulations of Apollo 13 (1995) and First Man (2018) to shame.

Overall, it’s a tidy (93 minutes), Cinéma vérité style doc, long on reproducing the sights and sounds of the Apollo 11 mission with a minimum of explanation and no narration. If bringing the past back to life is the goal of any documentary, the startling new video and audio of Apollo 11 sets the highest standard I’ve ever seen.

Any new documentary about American manned spaceflight is an exercise in somewhat wistful nostalgia: they document an era when we used to take on huge, improbable projects like this, apply the best minds on earth to the task, and make human history. There was a recent interview with a retired NASA official where he said that if the funding for space exploration had continued at the same pace as the Apollo program, humans would have landed on Mars by 1985. Alas.

We had relatives over and everyone watched with wonder-- except my uncle Jim, who had a big lunch and was passed out in dad's Barcalounger, snoring through the whole thing. I was annoyed with him at the time, but now I realize he had a half-good reason to be zonked out: For such a momentous event in world history it was not a particularly interesting one to watch. Neil's step onto the lunar surface was carried live, but it was a super-contrasty monochrome image. The networks carrying the moon landing used a lot of cheesy animation, simulations and talking heads to pad out the low-res NASA video feed. The astronauts had to return to the earth, with it's plentiful film processing facilities, with magazines of exposed 16mm movie film and 70mm still images to give us the iconic imagery we associate with the era.

|

| Live video of Armstrong on the moon looked like this. |

The media status for early manned spaceflight hasn't changed that much: Grainy 16mm and low-res video (some in color), backed up by more 16mm TV coverage. When documentary filmmaker Todd Douglas Miller set out to make a 50th anniversary tribute of the Apollo 11 mission, he started out with the same resources everyone else had since the Nixon era: The familiar stills and grainy news footage, the same warbling audio.

Then two remarkable archives of previously unseen and rarely heard content were discovered.

|

| The Mitchell AP65, very likely one of the cameras used to document the Apollo missions. |

|

| From the opening sequence: the Crawler delivering the Saturn v rocket to the launch pad. |

|

| The Saturn V taking off, in 65mm Todd-AO. |

Overall, it’s a tidy (93 minutes), Cinéma vérité style doc, long on reproducing the sights and sounds of the Apollo 11 mission with a minimum of explanation and no narration. If bringing the past back to life is the goal of any documentary, the startling new video and audio of Apollo 11 sets the highest standard I’ve ever seen.

|

| Neil, Mike and Buzz, about to board the Airstream to the stars! |

Labels:

1960s,

Anamorphic,

Aspect Ratio,

documentary,

Film,

Mars,

nostalgia,

technology

Tuesday, March 19, 2019

Monday, March 11, 2019

Monday, March 4, 2019

Box Office Report, no video this week

I am almost to busy this week to even tell you I'm too busy to do a box office report but as you can see, at least I can manage that much. Look at this though!

https://www.boxofficemojo.com/weekend/chart/

You can't stop Tyler Perry's Madea. Only Tyler Perry himself can.

https://www.boxofficemojo.com/weekend/chart/

| TW | LW | Title (click to view) | Studio | Weekend Gross | % Change | Theater Count / Change | Average | Total Gross | Budget* | Week # | |

| 1 | 1 | How to Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World | Uni. | $30,028,540 | -45.4% | 4,286 | +27 | $7,006 | $97,678,815 | $129 | 2 |

| 2 | N | Tyler Perry's A Madea Family Funeral | LGF | $27,062,332 | - | 2,442 | - | $11,082 | $27,062,332 | - | 1 |

| 3 | 2 | Alita: Battle Angel | Fox | $7,221,417 | -41.5% | 3,096 | -706 | $2,332 | $72,452,725 | $170 | 3 |

| 4 | 3 | The LEGO Movie 2: The Second Part | WB | $6,600,258 | -31.8% | 3,458 | -375 | $1,909 | $91,660,298 | - | 4 |

| 5 | 4 | Fighting with My Family | MGM | $4,661,991 | -40.3% | 2,855 | +144 | $1,633 | $14,916,612 | - | 3 |

| 6 | 11 | Green Book | Uni. | $4,573,320 | +114.9% | 2,641 | +1,388 | $1,732 | $75,782,931 | $23 | 16 |

| 7 | 5 | Isn't It Romantic | WB (NL) | $4,514,602 | -36.6% | 3,325 | -119 | $1,358 | $40,168,605 | - | 3 |

| 8 | N | Greta | Focus | $4,481,910 | - | 2,411 | - | $1,859 | $4,481,910 | - | 1 |

| 9 | 6 | What Men Want | Par. | $2,763,886 | -47.3% | 2,018 | -371 | $1,370 | $49,704,890 | $20 | 4 |

| 10 | 7 | Happy Death Day 2U | Uni. | $2,456,240 | -49.8% | 2,331 | -881 | $1,054 | $25,222,850 | $9 | 3 |

You can't stop Tyler Perry's Madea. Only Tyler Perry himself can.

Tuesday, February 26, 2019