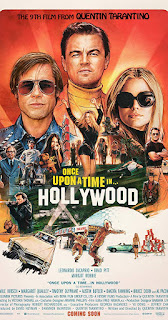

I went into

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood expecting not to like it that much: he burned me very badly with his cute switcheroo act with

The Hateful Eight, a film he touted as an epic widescreen roadshow movie but turned out to be a

blood-drenched, claustrophobic indie film that had no earthly reason to be in Ultra Panavision 70.

But after thinking about it for a while afterward, I have a grudging respect for this film.

Once Upon a Time is built around an original story, unusual for him: its not a pastiche or an homage or a dully executed re-make of some cheap exploitation film. It’s really him, talking directly to us and not through some faux-junk, schlocky exploitation genre— and God damn it if that isn’t refreshing. Quentin succeeds at his primary goal here: creating an alternate universe version of Los Angeles in 1969. He did a splendid job of it. The dialog is crisp, mostly lacking the big gobs of “Tarantino-speak” that bogged down earlier efforts, and the acting snaps as well. It’s a longish film, and his obsession with the trappings of the past often overwhelms his story, but more worth your time than any of his films since

Jackie Brown.

On to the notes!

Nostalgia: Once Upon a Time drowns in nostalgia, aching and wistful and angry at the passage of time that erased the treasures lovingly displayed onscreen. Quentin Tarantino is a filmmaker driven by desires— obscure action cinema, violence, glib dialogue, women’s bare feet. But this time his desire is the past.

His past, a past he has said was the favorite time of his childhood.

Once Upon a Time is Quentin the video-store clerk and kid who grew up in LA in the 1960s and 1970s, finally brought to his fullest. It’s a wishlist of everything he ever wanted to do in a movie as a kid, pattered out in his characteristic staccato: he wants to be a TV western star (Quentin Tarantino was named after Burt Reynold’s character in “Gunsmoke”). He wants to beat up Bruce Lee. He wants to change Hollywood history (more later). He wants to set an LP needle down right on the gap before his favorite song (this happens several times) and hear the KHJ and KFWB jingles ring out over an AM car radio again. He wants to make a movie with Steve McQueen and Michelle Phillips and Sharon Tate. He wants all he knew and saw and loved as a child returned to him.*

But most of all, he wants to go home to the past. You can feel it: his longing reaches right out of the frame. It’s all there in broad strokes: late 60s Hollywood Boulevard lovingly recreated; classic, unchanged locales like Musso and Frank and El Coyote visited. There’s a montage near the end of the film that gave one of the biggest thrills of the movie: night falls and long-gone business facades light up. There’s an old Der Weinerschnitzel, a Mission-style Taco Bell, The Cinerama Dome restored to its Pacific Theaters glory.

Tarantino is one year younger than I am, and I spent some time in LA around this time as well— down in sleepy suburban Lynwood rather than Hollywood, but I know these sights, the look and feel of the era. I’ll admit one of the strongest reactions I had to

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood was a strong desire to move into this film. I didn’t want to leave. I’m not sure if 1969 was a better world than 2017, but the version he showed us was simpler, shinier, and undeniably beautiful.

Two-person, one-character protagonist: washed-up star Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio) and his stunt-double/dogsbody Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt) are the inseparable pair at the center of the film. They make a very big deal out of the fact that Rick can’t function without Cliff, and vice versa. This makes it easy to pin this relationship as a Tarantino staple, tough guy male bonding. But it goes far deeper than that

. Rick and Cliff are the same character. They cannot exist outside of the definition they have for each other. The two characters span one complete male personality. Rick is insecure, weak, vain and sensitive (he cries like three times in the film), but also talented and ambitious. Cliff is taciturn, strong, highly capable and practical, but also lacks ambition to the point he is content to live in a wreck of a trailer in North Hollywood. A lesser effort would have these traits embodied in one overly complex, somewhat unbelievable character: in

Once Upon a Time this one character is smeared over two individuals, yin and yang, completing each other in all ways, functioning as one complete person. This sort of split character has been done in other films, but usually the other way: in biopics they make they take handfuls of real historical figures and smoosh them into one character.

History and the Unreliable Narrator (mild spoilers): Once Upon a time in Hollywood follows three intertwining storylines, much like

Pulp Fiction but without time-shifting tricks: Rick and his buddy Cliff, trying to re-start a failed Hollywood career; Sharon Tate’s arrival in Hollywood, and— lurking like an evil portent— the Manson Family, biding their time in an abandoned movie ranch in Chatsworth, waiting for their call to the stage.

Anybody familiar with recent history knows what happened the night of August 8, 1969: Four members of the Manson Family entered the house on 10050 Cielo Drive in the LA hills and murdered everyone inside, including actor Sharon Tate. Not to give away anything specific, but this is not what happens at the end of

Once Upon a Time. Something completely made-up happens.

Quentin Tarantino has done this sort of “alternative historical fiction” thing before: he killed the living hell out of Hitler in a French movie theater in

Inglourious Basterds. And by all means he has every right to do so: he’s the storyteller here and he has a right to re-tell historical events any way he wants to. When you get right down to it, every filmmaker who ever shot a narrative film is a total and complete liar. You can plot a line straight through the relative level of reality in any filmmaker’s work, from hyper-real (

Zero Dark Thirty, The Grapes of Wrath, HBO’s

Chernobyl) to utter fantasy (

Toy Story 4, Lord of the Rings, Top Gun) with lots of shading in-between. And the hyper-real ones are still mostly made-up hooey.

But the tall tale Tarantino is spinning at the conclusion of

Once Upon a Time does something very strange. If the terrible thing that is supposed to happen on the night of August 8, 1969 doesn’t happen, what was the point of two-thirds of the film? In other words, if you showed this film to somebody with NO IDEA of the history Quentin Tarantino is re-writing, what would she make of it? She would sit through long sequences of Sharon Tate wandering around Los Angeles, shopping, seeing herself in a movie theater in Westwood. She would see long sequences of Manson Girls wandering around Los Angeles barefoot, hitchhiking and hanging around Spahn ranch. But they never really connect: all the long minutes of foreboding and build-up are dissipated in a standard Tarantino gory ending. Our historically ignorant movie viewer would leave the screening wondering why those other sequences even exist.

Does a filmmaker owe fidelity to historical facts? I don’t know. What I do know is this film will be seen by people 50, maybe 100 years from now. The Tate-LaBianca murders will no longer be a part of living history: to these future viewers, they’ll be as familiar with the actual events as we are of the details of the murder of Stanford White in 1906. Which is to say they may very well accept

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’s ending as actual history. This is how history gets distorted: it does not seem important now, but we owe some debt to the future to tell the truth.

*Quentin Tarantino put himself in this film twice, even though he had no cameo. In one segment Rick Dalton is resting between set-ups in a western backlot set next to a precocious child actor (Julia Butters). She is roughly the same age QT would have been in 1969, and you can hear him talking through her as she engages Rick in some positive affirmation. Later in the film one of the characters announces a move to “a condo in Toluca Lake,” likely the same one occupied by Jimmie and Bonnie 25 years later in

Pulp Fiction (1994).